Realizing that this subject will not be of interest to everyone, I apologize. There are many people out there in the world however that legally and responsibly own firearms and who can still respect these as implements of recreation – not as devices used just for killing. I personally am fortunate enough to live in a remote, unpopulated area of the American southwest. With ease I can move myself many miles from civilization, and shoot to my heart’s content without disturbing other people. Not having hunted in years, I don’t persecute nature’s critters, which is not to say that I would not if I became hungry. Collecting guns and target practice are hobbies that I intend to continue to enjoy until I lose interest or unless my society ordains to completely confiscate these privileges from responsible citizens. “Reloading” is a skill set that an overwhelmingly large percentage of the shooting public can neither do nor is willing to perform. With reloading equipment an enthusiast can save much money while replenishing his supply of ammunition and with expertise he can produce better and more accurate ammunition than he can buy in the marketplace. The subject of this post is to focus on a narrow set of rare, somewhat frivolous and purely recreational ammunition that simply cannot be purchased, but must be handmade.

Wax bullets are most suitable for indoor pistol target practice. These projectiles are made from melted paraffin, candle or bee’s wax and they are propelled only by a primer – no powder is used. These projectiles are not especially accurate, they have a short range and are hardly lethal but they should be used with caution. The primer alone provides enough propulsion to send the wax projectile through the side of a cardboard box or aluminum soda can at close range.

To begin, perhaps a dozen or so spent cartridge cases are “de-primed”. Next the wax or paraffin is melted and then poured into a pie plate or metal lid to the thickness of about 12mm (or ½”). It takes a while for the paraffin to solidify. Before the wax completely hardens – at a point where it is malleable and not sticky, the empty and de-primed shell cases are pressed down into the wax, cutting off plugs which seat flush with the top of the cases. After the wax has hardened the case can be primed with a new pistol primer and the cartridge is ready to go.

* Wax slugs can be used in shotguns also. Using wax in a lead ‘slug mold’ perhaps, these toy bullets are also driven only by propellant from a primer. Shotgun primers are much more energetic than pistol and rifle primers however. A shotgun primer combined with a wax shotgun slug (lots of mass) creates enough kinetic energy to easily penetrate sheet-rock walls. These should be used outside.

At least one company still makes plastic practice ammunition. Available in rimmed (revolver type) calibers .38 / 357 and .44, these projectiles are reusable. Designed to use the larger and more powerful Magnum pistol primers, these can reach a velocity of perhaps 300 ft/sec.

If one has a lead bullet mold he can make durable, reusable indoor practice bullets from hot glue.

There is a fair selection of reloading tools available, but these tools are not numerous because demand is not great. On the low end a simple kit like the one imaged above cost about $30. Such kits are available for almost any rifle or pistol caliber and although a bit slow they are perfectly adequate. The original once fired brass might need to be reshaped once in the resizing die for the cases to seat in the gun’s chamber comfortably. Thereafter for wax, plastic or hot glue bullet reloading only the primers need to be replaced.

Next is a foray into the lost art of making “ultralight” cartridges. The only kind of commercial ammunition available for high powered hunting rifles is maxim power / high velocity ammunition. Such ammunition can be hard on the rifle and in larger calibers can even become unpleasant to shoot. Because of the prohibitive cost of such ammunition but also sometimes because of the recoil, many hunters do not practice enough to make themselves good marksmen. Reloaders (using researched data tables from books) have direct control over velocities, chamber pressures, recoil and ballistics. In the past reloading publications contained more information dedicated to what are properly called “light” loads. Light loads are much more pleasant and economical to shoot in a high powered rifle. Light loads typically involved using cast lead bullets that are driven at lower velocities to prevent deforming the bullet or the smearing lead along the sides of the barrel. Typically the bullets were cast from hardened lead (alloyed with tin and antimony) and swaged (squeezed to size) with alox (waxy lubricant) and stamped with a brass or copper gas check on the base. Well, “ultralight” ammunition is lower in velocity still and you will not find its reloading information in any modern handbook. For just a trifling cost ultralight ammunition can turn a loud and imposing hunting rifle into a more recreational device that is pleasant to use and much less noisy.

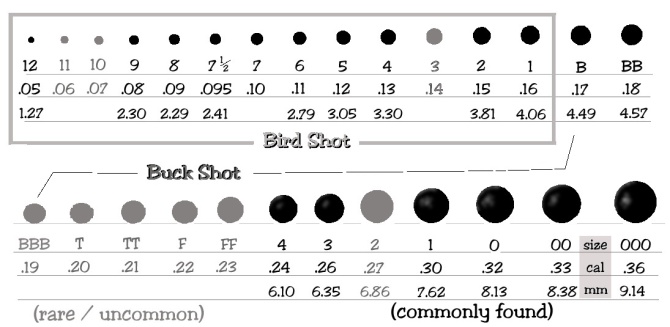

Above is an image of a .30 caliber cartridge loaded with a #1 Buck shot (7.62mm / .30 cal) lead ball. Just a tiny bit (1 to 3 grains) of fast pistol powder is used as propellant in the freshly primed case. The ball is seated into the case mouth by hand pressure alone, excess metal being easily sheared off by the brass case mouth. A little cotton or other fluff can be inserted over the top of the powder to keep it down close to the primer in such a large casing. Since repetitively measuring such a small amount of powder is impractical a home made powder scoop can be made from a spent .22 rim fire case. A .22 short powder scoop with a piece of wire or paper clip soldered on as a handle, will throw about 2.2 grains of “Bullseye” powder. A similar scoop made with a .22 long rifle case would throw about 3.0 grains of Bullseye. Slower burning pistol/shotgun combination powders like “Unique” and “Hi-Skor 700x” will also produce fine ultralight loads.

Ultralight loads can be produced for any pistol or rifle caliber. Their purpose is to act as pleasurable short range, low danger and low noise “plinking” ammunition. The whole point of ultralight loads is lost if too much propellant is applied, because accuracy will fail. Modern rifles have barrels with high rates of rifling twist, which is needed to stabilize jacketed bullets at very high velocities. The old flintlock rifles used two centuries ago had a very slow rate of rifling twist (something like 1 turn in 66 inches) which was needed to properly stabilize or impart spin to a patched round ball. Because a round ball makes so little surface contact with the rifling, the velocities of ultralight loads in modern rifles need to be kept very low. Ultralight cartridge loads are much less lethal than regular ammunition but they are not “toy” loads and should be treated with respect.

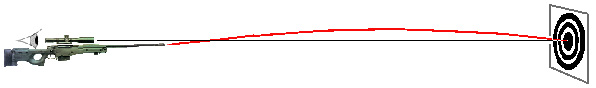

A scoped deer rifle can perform fairly accurately with ultralight ammunition at a distance between 50 feet and 80 yards. The line of sight from a gun site or scope is a very different path from the flight path or trajectory that a bullet takes. The bullet actually crosses the line of sight twice; once at a close distance and then again downrange depending upon the elevation of the sights. For a typical high-powered and scoped hunting rifle that is ‘dialed in’ for accuracy at 300 yards, a normal projectile might first cross the line of sight at 100 feet.

In the shot chart above, #1 buckshot is .30 caliber in size. The #1 round ball will produce ultralight rounds in .30 cal firearms, including: 30-30 Win, 30 M1 Carbine, 300 Savage, 308 Win, 308 Norma, 7.5 Swiss, 7.62 Russian, 30-40 Krag, 30-06, 300 H&H, 300 Win Mag and 300 Weatherby Mag, not to mention several antique pistols chambered in .30 cal. Slightly over-sized bores with a .311 diameter (like the British 303, Jap 7.7, 7.62 Russian and Russian 7.62 x 39 cartridges) can be accommodated with the #1 buckshot ball also. Round ball molds for size F, FF and #2 are rare or do not exist, so the only common rifle or pistol calibers not matched to a popular buckshot caliber are the “22’s” and the .270 Win and .270 Weatherby cartridges.

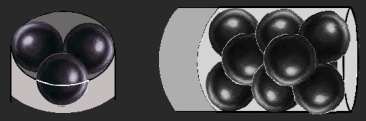

“Double ought buck” was once very common on the American frontier and in English vernacular because “00 size” allowed these respectively hefty shot to be stacked densely and efficiently within a 12 gauge shotgun hull. Nine heavy #00 Buckshot pellets are commonly placed in a 2 ¾” – 12g shell, and 12 or even 15 will fit in a 3” shell. For the homesteader on the American frontier shotguns were more versatile and more numerous than rifles and they probably brought home more meat.

(edited 8/15/2018)

Caliber / Gauge / Bore

Caliber is the inside dimension of a rifle barrel. In the U.S. the caliber measurement is generally taken from groove diameter (low points) and not the bore diameter (high points or lands) of rifling. The very common a 22 caliber rim fire cartridge, has a bullet diameter of 0.22 inches (or 5.58 mm).

Gauge is the number of lead balls – of a particular bore diameter needed to weigh one pound. The nominal inside diameter of a 12 gauge shotgun is 0.73 inches (18.5mm), so it takes twelve lead balls of this diameter to weigh one pound. While a 12 gauge shotgun could easily be called a 0.73 bore shotgun, a .410 shotgun actually has a bore diameter of 0.41 inch (therefore it is not 410 gauge). It would take about 67 balls of 0.410 diameter to equal one pound but the name “67 gauge” just never caught on. Incidentally the .410 bore shot-shell matches up well with the .45 Colt and .45 Long Colt cartridges and some firearms are modified to fire both. Cannon balls were usually designated or described by the weight in pounds of a cast iron ball that fit the barrel.

locations: Dubuque, Berlin, Baltimore, Philadelphia

Before the 18th century, molded musket balls and bird shot used in muzzle-loaders was a far cry from being uniform. In 1782 an Englishman invented the first shot tower, where molten lead fell a long distance and became well shaped and solidified before its travel was terminated, usually by a tank of water. Accurately rounded, uniform spherical shape meant that bird-shot, buckshot and rifle-balls flew farther and straighter. “Chilled shot” made in such a tower was also harder than an alternative shot that cooled slowly. Hardness helps reduce the deformation of lead pellets as they percuss or impact against the walls of a shotgun barrel. Whether for bird-shot or rifle ball, the hardened and well rounded lead shot at the bottom of a tower was screened, sorted and organized according to size.

Shot towers progressively became obsolete over the years as simpler methods for making shot were invented. Several towers remain around the globe and are historic landmarks because they were so well built that it was a shame to tear them down. Most were stoutly made of brick because of the weight that needed to be supported and logistical problems of getting heavy molten lead to such a high elevation from the ground. Usually the furnaces were at the top. A classic example is the Phoenix shot tower in Baltimore, Maryland. It was built in 1828 from 1.1 million bricks and has cylindrical walls that are 4.5 feet thick at the base. In 1878 the tower caught fire, destroying the interior of heavy wood scaffolding and elevator and bringing 15 tons of lead down to the floor. The brick walls were not damaged by the fire though – so the interior was rebuilt.

Hand loaders often smelt their own buckshot and rifle balls. Since lead turns to liquid at 621º F (327º C) in can be easily melted in a pan or pot, over a campfire or a gas range. Single or multiple cavity hand held bullet molds quickly turn out a small supply of projectiles. Modern commercially made lead balls and buckshot start as plugs cut from thick lead wire and then forcefully swagged and shaped in a hemispherical mold. Modern bird-shot used for waterfowl is usually compression molded from steel, bismuth or some other non-toxic alloy.

Since the 1960’s small commercially made lead bird-shot is probably created using the simple “Bliemeister method” which involves quickly coating a dribble of molten lead in a hot viscous liquid and then letting it roll down an inclined plane before falling further into a reservoir of cooler liquid. The fall is a very short (2′ to 4′) and automotive antifreeze or water plus “water soluble oil” are typically used as the viscous liquid.

This website is mostly a stroll-by for all of the data you wished about this and didn’t know who to ask. Glimpse right here, and also you’ll positively uncover it.

Thanks for the sensible critique. Me and my neighbor were just preparing to do some research on this. We a grabbed a book from our area library but I think I learned more from this post. I’m very glad to see such wonderful information being shared freely out there.

WONDERFUL Post.thanks for sharing.. 🙂

I am so happy to read this. This is the type of manual that needs to be given and not the accidental misinformation that’s at the other blogs. Appreciate your sharing this best doc.

I’d like to try #2 buckshot for ultralight loads for my 256 Newton. The only source I’ve found so far for #2 buck sells hard lead (some percentage of antimony). I wonder if you have experience with that and whether there’d be a problem using un-sized cases to make it easier to shove the ball into the case neck. I’m also curious about leading of the bore when using buckshot for projectiles in rifles.

I am unaccustomed to receiving replies from real people. Usually I must sort through a bunch of spam comments.

I’ve cast quite a few lead bullets in the past. The Lyman manual has a recipe for casting lead composition, but it seams to have relied upon a dubious antimony / Linotype standard. Newspapers (I worked in a newspaper’s old fashioned print-shop in the 1970s) reused their lead continually. Old reloading books may refer to “Linotype” as possessing uniform antimony-lead content but consider that previous to the 1950 or 60s that there were lead using newspapers all across the country. Surely some of that Linotype was adulterated with softer lead.

Antimony serves to harden lead like sand and gravel preform in concrete. Wheel weights used to balance new tires contain a high amount of antimony (about 9%). Authentic Linotype is considered too hard for casting bullets (@ 84% lead, 4% tin and 12% antimony). Lyman’s preferred recipe (called #2 alloy) is 90% lead, 5% tin and 5% antimony. To get these metals to mix right and not separate when you smelt them together you need to know how to flux properly.

Cast bullets need to be hard in order to reduce leading of the barrel. Beyond speeds of 1,100 fps you would be well advised to use a copper or brass “gas check” on the bottom of the bullet. At the very low velocity these ultralight bullets will be traveling though, leading of the barrel should be a very minor concern. You might prefer actually or need to use plain soft lead because that will shear off easier as you press the ball into the case neck – with thumb pressure. I see no problem with using un-sized brass, as long as the cartridge will chamber.

I’ve recently acquired several boxes of .30 Newton reloads and empty brass, myself. I’m hesitant to sign up with gunbroker.com to try to sell it.

Hi! Would you mind if I share your blog with my facebook group?

There’s a lot of folks that I think would really appreciate your

content. Plsase let me know. Cheers

Maintain the excellent job mate. This web blog publish shows how well you comprehend and know this subject.

Pingback: bp51vcdHyV bp51vcdHyV

Good to see that there are still helpful blog sites out here, thanks.