_ Although potentially a messy and inconvenient chore, the ability to procure one’s own food by slaughtering an animal is an essential skill for the well rounded and self sufficient individual. This post offers some brief suggestions on how to butcher and process meat properly. If fresh meat is not to be cooked and consumed immediately, there are some time honored meat preservation methods to choose from. Jerking (drying), canning, or salt curing & smoking methods for instance.

_ Freezing may have become the most convenient way to preserve meats since WWII but these meats will still begin to deteriorate in other ways if they are left in a freezer too long. From a bacteriological viewpoint, meats and other frozen foods should normally remain safe to eat indefinitely if stored at an uninterrupted, non-fluctuating 0º F. However the optimum shelf life for most frozen foods is only from one month to a year – before food quality begins to suffer from freezer burn or loss of color and flavor. Unfortunately frozen meats are entirely dependent upon generous and continuous, uninterrupted sources of electricity.

_ Processing, curing and preservation methods may differ between animal species. Raw fish for example, which begins to deteriorate very quickly can still be canned, smoked or turned to jerky. The precautions for fish preservation differ by being more urgent. Traditionally larger animals were butchered only when the climatic temperature dropped to levels that retarded meat deterioration. It is no mystery why today’s deer, elk or moose hunting seasons begin in the fall. When butchering large to medium animals like cattle, deer, sheep, goats or pigs, the first significant priority is to reduce the carcass’s internal heat. The best way to do that is to bleed it, remove the skin and split the carcass. There are probably as many detrimental fungi and bacteria lurking inside the meat as there are outside it. The quick reduction of internal body heat in a carcass is the first step in reducing undesirable microbial or enzymatic deterioration of meat. Snow banks and cold concrete floors can act as desirable surfaces in this heat reduction endeavor.

pre – 1911 “Reefer car” / Wikimedia commons

Refrigeration

In modern industrialized nations, refrigeration has changed our diet and has permitted the manifestation of the modern supermarket. In urban areas, before refrigeration came along, fresh meat could be immediately consumed by a large populace, before it had a chance to spoil. Before refrigeration and outside urban areas, meat harvesting was traditionally preformed in the fall or winter. Cold temperatures assist in processing and preserving meat by discouraging bacterial activity both inside and out. A century ago the availability (or not) of fresh meat and vegetables was dictated by seasonal and climatic temperature. Initially commercial meat processors and brewers relied upon refrigeration from wintertime ice blocks cut from lakes and stored in sheds. Properly ice ventilated “refers” or refrigerated railroad boxcars began shipping meat, dairy, vegetables and beer around the U.S. in the 1880’s.

US National Archives image /1917-18

Although invented a few decades before on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean, artificial refrigeration did not find successful application in the meat packing industry until the turn of the century and its accompanying delivery of commercial electrical power. By 1914 artificial refrigeration was the norm for perishable food wholesalers and retailers. Like milk or newspapers arriving on the doorstep, ice blocks were delivered to the ‘iceboxes’ of most urban homes. In the 1930s, newfangled electrically powered household refrigerators appeared, but since coinciding with the ‘Great Depression’ – only the affluent could afford them. Rural areas would wait much longer for delivery of electrical power. After WWII, household refrigerators finally became common for the rest of the nation.

No longer restricted by the seasons, today we can buy fruits or vegetables “out of season” because they are maintained in a chilled state while being shipped from far away. Likewise, supermarkets and groceries presently offer us plentiful supplies of fresh cut meats; due to the marvels of electricity, artificial refrigeration, and oil dependent transportation supply chains.

Vocabulary

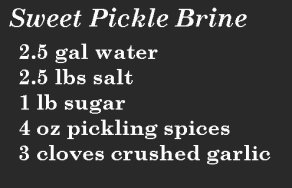

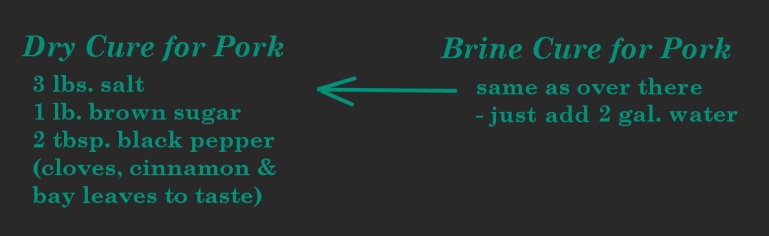

Curing– can be a vague term because it is a process where so many ingredients or methods used can apply. The only essential ingredient in a cure is salt (plain NaCl / without iodine). Salt draws moisture out of the meat and it shuts down most microbial activity. Although humans like other animals require salt in their diet, and at moderate levels it may enhance taste; salt has actually been such a historically valuable trade commodity because of its capacity to preserve meat. “Corning” is the process of treating raw meat to dry salt crystals (any type of salt: pickling, rock, kosher, dairy or canning – but not iodized which may cause discoloration). There are quick acting “dry” cures where salt crystals and perhaps additional dry spices are packed directly around the meat. “Wet” cures are essentially brine solutions in which meat is submerged and soaked. In either case salt causes water to be drawn out of both muscle tissue and out of undesirable microbes by osmosis. “Pickling” meat generally refers to using a curing mix or solution that also contains sugar and extra spices. Sugar or honey might be included in a cure to counteract the harshness of excessive salt and to keep meat moist and tender. Some spice combinations don’t work – garlic and black pepper can overpower a cure. A “hard cure” implies a process involving both salt curing and long term exposure to preserving pyroligneous acid from creosote in wood smoke. A hard cured ham or slab of bacon can become very dehydrated over time. “Ageing” is a term usually reserved for beef. Quality, tender “premium” beef is sometimes “dry aged” and is usually only to be encountered in a good restaurant. The general public can only purchase a compromised product from the grocery, referred to as “wet aged” beef.

“Jerky” is an Anglicized version of a previously Spainglacized (?) version of a original Incan word: “ch’arki” – meaning dried meat. Although any meat can be “jerked”, venison and lean beef respond best to the process. Obviously low air humidity is necessary for the process. For simplicities sake the raw meat can be dressed into the form of large and wide, but thin slabs before being introduced to the cure. Either a dry salt cure or wet brine solution should be applied to the meat. Afterwards the individual slabs are cut into thin strips and spread on a rack. Whither exposed to sunshine or spread on racks inside, the meat should dry enough eventually, to snap rather than fold when it is bent. A dry cure might produce results more immediately, because a brine-cured meat might soak in solution for a 3-6 day period before being removed for drying. Below is an example brine recipe that might as easily be applied to a ham as it is to jerky.

Canning

Naturally, meat can be canned at home. This post won’t delve very far into the details of canning but the main thing to remember is that any improperly canned foods are subject to developing botulism. Clostridium botulinum is a curious, heat resistant bacterium that despises oxygen. So while a host of bacteria like salmonella, E.coli, and listeria monocytogenes are killed at boiling water temperatures (100 deg C / 212 deg F), botulinum spores locked within an airtight can, bottle or glass jar – would not be killed. To insure canned food is safe, home canners must maintain an elevated temperature for an extended time. By using a large specialized pressure cooker known as a “pressure canner”, the cook is able to reach an abnormal 115.5 deg C / (240 deg F) temperature by essentially doubling the atmospheric pressure first. To be safe, that high temperature is maintained an hour to an hour and a half.

Fish

The Carib Indians were smoking fish over fires to drive flies from drying fish jerky when Christopher Columbus discovered these “Indians” in the New World. Almost every type of fish responds well to curing and smoking but fish with a high percentage of oil (greater than 5%) do not air dry well. Oily or fatty fish that do not dry properly are often preserved by “corning” instead. Three to four generations ago many people in coastal regions continued to salt pack fish away in wooden barrels in the same way others inland might have stored “pork butts” or bacon away in barrels. Requiring no refrigeration, freshly cleaned and dressed fish were sprinkled with corning salt and then stacked in a keg. After about four days the salt pulls enough moisture from the fish to create its own brine solution. Then the fish are rotated and re-stacked in the barrel, more salt and fresh water are added until the brine solution covers all the fish. The fish should be firm when the salt has completely penetrated through the flesh. Before consumption, the excess salt is washed and rinsed away, and fish are soaked and refrigerated in fresh water overnight.

* In the Great Lakes region people have occasionally contracted ‘broad fish tapeworm’ – from eating uncooked pickled pike, walleye or other predatory type lake fish. Freezing the fish before pickling eliminates this threat (as does cooking).

Fermented Fish

Several cultures have resorted to fermentation as a method of fish meat preservation. In the Mediterranean, anchovies are allowed to ripen for at least one half of a year before they are considered ready. Orientals might ferment anchovies, shellfish, squid or shrimp for more than a year to create that dark brown “fish sauce” they cook with. Scandinavians might eat “Hákarl”, “Surströmming” or “Rakfisk” which are so odorous as to send normal people into flight. Eskimos not only ferment fish but might toss birds, sea lions, walrus, whale parts or anything else with protein into the same earth covered fermentation pit. Fish fermentation works because most bacterial activity is halted as the level of acidity increases.

Poultry

The same preserving techniques used for other meats can also be used on fowl. Since fowl seems to dry rather quickly, brine curing solutions are preferred to dry ones. Turkeys and chickens are seldom hard cured (smoked) whereas ducks and geese can be because of their higher fat content.

Beef

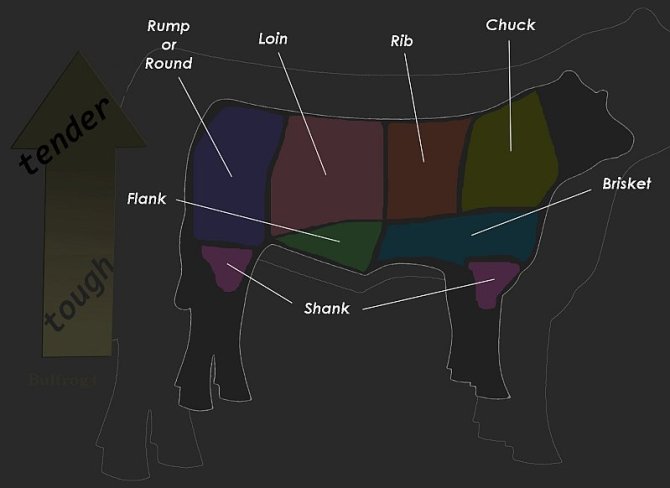

Driving out excess moisture from meat deprives bacteria and fungus a furtive environment to grow. While salt cured pork hams and bacons may hang for years in a smokehouse, the primary purpose of a salt cure and of smoke is to dehydrate and preserve. Only cheaper cuts of beef from the chuck, rump or brisket are improved by salt cure and smoke preservation. Cures for beef will still employ salt, but are also sweetened usually with something like brown sugar, maple syrup, molasses or honey.

Pastrami, corned beef and ‘bully beef’ are salt cured and packaged or canned without being smoked. Beef being a larger animal, has about twice the number of basic or primal cuts as does pork. There is little agreement or standardization between cultures or countries on how a beef should be cut. Thanks to refrigeration, beef can be deliberately aged to improve its character, but pork is seldom treated more than a couple of days this fashion.

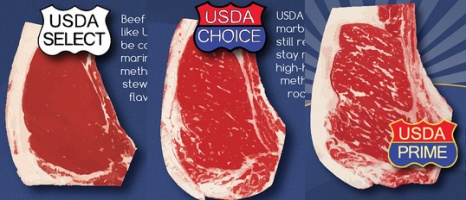

Unless you go to some effort, the only way an individual is likely to encounter aged beef is to order it in a good restaurant. The public has no access to properly aged beef in a grocery or supermarket. Today meatpackers just inject the beef riding conveyor belts, with chemicals like sodium phosphate- which changes the pH of meat protein and allows it to hold more water and weigh more. “Still wiggling” so to speak, the wet and fresh steak or what have you undergoes treatment with other chemicals, gasses and perhaps radiation, before it is hermetically sealed in shrink wrap and crated for shipment. While in transport to a retailer, this commercial beef with which we are acquainted is euphemistically referred to as “wet aged” beef.

chopped from U.S. Department of Agriculture poster

“Dry aged” beef on the other hand is where a side of beef hangs in a refrigerated meat locker for many weeks as it tenderizes. The meat locker is maintained just above freezing (34 – 40 deg F), allowing oxidization of fats and enzymatic breakdown of muscle proteins to occur. Meanwhile gravity pulling upon a side of beef is considered to assist in fiber tenderization. Only superior beef carcasses with good marbling (streaks of fat interlaced throughout the meat) are subjected to the expense of dry aging. Dry aging allows time & environment for enzymes to break down muscle proteins into shorter fragments. Exposed to free air, fat oxidizes and adds flavor to the meat. Since the process requires extra time, storage space, electrical refrigeration and causes a split carcass to loose a good deal of weight through dehydration –aged prime beef cuts are uncommon and expensive.

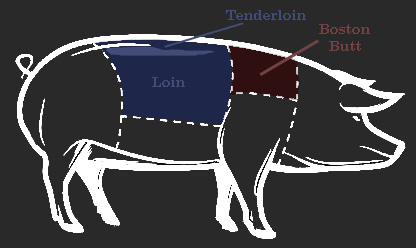

Processing Pork

Pigs are very efficient animals to farm for slaughter because the majority (>87%) of their weight is converted to food. A pig’s skin is often converted to food whereas a cow’s skin is not. Pork lends itself better to salt curing preservation than does beef or large, lean wild game. On the American frontier the hog was a cost-effective animal that was almost indispensable to early settlers. Pigs thrive in most climates, eat almost anything and reproduce quickly. With just a few pigs, farmers could feed their families through the winter, sell some or stash some extra meat away in storage and still have lard leftover to make things like candles or soap. (* For candles, alum & saltpeter were added to harden tallow.)

* Noting the Jewish and Islamic taboos on eating pork, the restrictions probably made perfect sense to earlier civilizations in the warm Middle East. Pigs can carry several types of parasites or viruses. Trichinosis comes to mind but this encysted larva of a parasitic roundworm might be found in almost any type of wild mammal also. Omnivorous pigs do have a more basic and quicker acting digestive system than do cattle (or humans), and they have no sweat glands to expel pollutants they might have ingested. Pork is one meat that definitely should be cooked well. That means reaching 71° C (160°F) temperature down deep next to the bone in a piece of meat. From New Guinea to Hawaii the ancient Polynesians cooked pork in a pit; usually to a point where the meat just fell away from the bones.

People who raise pigs for easy slaughter might prefer their shoats to be of manageable scalding size – say 45kg (100 lbs.) or so. Immediately after killing a pig, “sticking the pig” refers to puncturing its carotid artery with a knife to let the blood run out quickly. Since retaining the skin is often desired, the easiest way to remove the hog’s hair is probably to scald the carcass in boiling water. Next the hair should be scraped off with a blunt edge tool similar in sharpness to the backside of a butcher knife. Afterwards flame can be used to burn off any remaining individual hairs. Actually surrounding a pig’s carcass with dry straw and setting the pyre afire is an ancient alternative to hair removal by scalding.

After scraping, the pig’s carcass is often hauled up into a tree by its separated hind legs. This allows the blood and other fluids to drain, allows for easy separation of the offal and facilitates simple splitting of the carcass down its backbone. Splitting down or through or beside the hard vertebra requires a tool like a hacksaw, reciprocating saw or heavy butcher’s (not a flimsy Oriental type) meat cleaver.

* Butchering can be preformed on a flat table also. The following link to a video shows a skilled butcher doing just that. Whole Pig Butchered – Video

*Another video showing where bacon is located and how it is cut.

After being processed to the point of being split into halves or smaller “primal cuts” there are several avenues to take: as in choosing between barbecuing, canning, freezing, etc. This post is concerned with exploring the old fashioned smoke & salt cure methods of long term preservation. The majority of traditional curing recipes were intended to complement pork coincidentally.

Typically a ham or shoulder might be packed in dry salt cure (1 lb. for every 12 lbs. meat) and remain that way for at least (2 days per lb. of meat). The same cut would remain submerged for about twice that long for a brine cure – or a month max. Thinner bacon or loin cuts would differ by requiring about half as much salt cure.

For the thick ham and shoulder cuts a “brine pump” is very useful in preventing rot, by injecting cure solution down deep next to the bones. Length of smoking period is a matter of taste, with 4 days being a minimum and no limit on a maximum exposure. Virginia hams, already cured, might yet hang in a smokehouse for years. Back in Colonial American days these hams were valuable and articles sometimes needing protection from theft.

* “Boston Butts” or cuts of pork do not come from the rear end of a hog – just the opposite. The name comes from colonial America and the way that these tender shoulder cuts were packed for export and in salt, within smallish or middling sized wooden kegs (the cask themselves were referred to as butts).

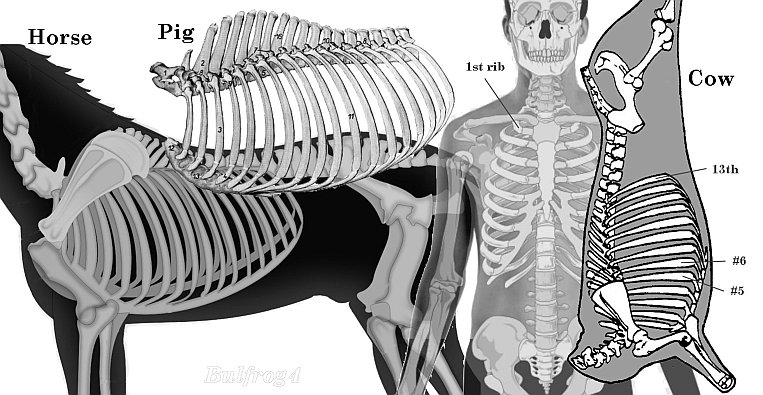

Usually an experienced butcher will separate the loin and belly sections from the shoulder (top butt and picnic) section by cutting down between the 5th and 6th ribs. Ribs are counted, beginning from the neck. The loin region ends at the last rib. The tenderest meat from either a pig or a cow comes from the tenderloin. The tenderloin is a long muscle that doesn’t get much use, and it runs inside the rib cage and alongside the spinal column. The “Filet mignon” cut steak comes from the smaller end of this muscle (the end further away from the hip). The expression “Living High on the Hog” refers to eating or being able to afford the most tender and therefore most expensive cuts of meat. As with cattle or any similar herbivore, meat generally gets tenderer as the distance from the hoof grows.

hash of 4 altered public domain images

Ribs

Horses normally have 18 pairs of ribs, but occasionally 19 pairs. The first eight pair of horse ribs are “true ribs” and the other ten are “floating ribs”. Pigs have 15 to 16 pairs of ribs – depending upon breed. For comparison humans generally feature seven “true” plus five “false” ribs, for a total of 12 rib pairs; except for an occasional human who may possess a pair less or a pair more than normal. Cattle have 13 pairs of ribs. “Chuck” cuts of meat come from the area surrounding the first five ribs on a side of beef. In the U.S., “Rib” cuts of beef come from the area between rib #6 and rib #12. The last or 13th rib marks the beginning of the loin region.

Sausage

The bits and scraps of meat and fat left over after butchering are not wasted but put into sausage. Traditionally the small intestines of the animal in question were washed carefully and stored in brine until used as the casings for stuffing. Cleaning intestines is a tedious job as both sides have to be carefully scraped of fat and mucus. Everything must be rinsed several times. Someone today might opt to purchase artificial casings or perhaps purchase real hog or sheep casings on-line or from a butcher.

Any type of meat can be used alone or in combination to make sausage. The happy balance between meat and suet in sausage seems to be somewhere around 2 parts lean meat to 1 part fat. Too much fat makes a greasy sausage that shrinks, while too little makes hard and dry sausage. Sausages can be hard cured and preserved for long periods, eaten immediately or frozen. Seasonings to avoid if freezing sausages would be garlic, sage and salt. Somehow the freezer makes the garlic tasteless and causes the other two to produce bad taste.

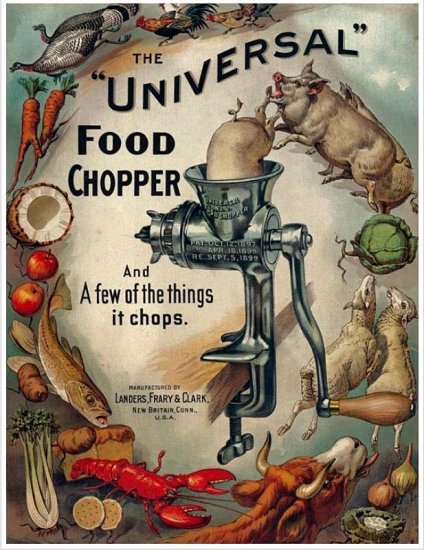

Besides casings the only other item needed to make sausage is a machine to grind up the meat. Food processors can perform this function but leave the particles too small. Expensive electric meat grinders perform admirably but are overkill for the occasional homespun sausage maker. The ideal sausage grinder for occasional use might be a hand cranked model, invented over a century ago. Smaller black & white reproductions of this approximately 117 year old poster below were probably placed in mail order catalogs. A funnel shaped attachment for stuffing casings accompanied the product. Copies or clones of this chopper are still being manufactured today.

Disease, toxins, worms and other nasties

Toxins or “biotoxins” are the poisons created only by living cells or organisms (all other poisons are correctly referred to as toxicants). Some pathogenic viruses, bacteria or fungi may require oxygen, while others do not. Acidity or the lack of, radiation like x-rays or UV light, freezing temperatures or high cooking temperatures and chemicals like salts, can all deter the detrimental effect of biotoxins in food. There are at least two hundred different known diseases or maladies, transmitted through food to worry about. Only a few short descriptions are listed here…

Clostridium botulinum which is responsible for botulism, is killed or inhibited by saltpeter (NaNO3 or KNO3), oxygen and high cooking temperatures. The most lethal neurotoxin ever discovered by mankind is named after a Latin word meaning – sausage. “Sausage poisoning” was once more common than it is now. A can of improperly cooked peaches may produce botulinum toxin. Although it can kill quickly, contracting botulism these days is very rare, something like 10 cases a year in the U.S. <see Alaskan Eskimos> The bacterium is found throughout the world in the soil and in untreated water. Some vain people actually pay a cosmetic dermatologist to inject this deadly protein into their face <see Botox> , where it has the effect of weakening or paralyzing facial muscles and removes wrinkles. The toxins created by this bacteria are inactivated by cooking to 160 deg. F. The bacteria itself is killed by 175 deg. F temperature but the dormant spores themselves won’t be killed until 250 deg. F is reached.

Salmonella is caused by eating food contaminated with animal feces.

Campylobacter jejuni is the most common cause of bacterial foodborne illness in the United States.

Listeria or Listeriosis is caused by the Listeria monocytogenes bacteria and is the third-leading cause of death among foodborne bacterial pathogens.

Escherichia coli (E. coli) are bacteria that live in human and animal intestines.

Trichinosis is a fairly rare (now) parasitic roundworm disease, caused by eating undercooked meat containing the worm’s larva. New strains of this parasite have been discovered that are found even in birds and crocodiles.

Toxoplasma gondii is a parasite that is the second leading cause of deaths attributed to foodborne illness in the United States. It is one of the more common parasites in the world and affects about 1/3rd of the human population. The parasite goes to the brain and forms cysts. Laboratory rats affected by toxoplasma gondii loose their innate fear of cat urine odor and the males begin to produce more testosterone.

Hepatitis E is a liver disease caused by a virus transmitted by fecal contamination in water or food supplies.

Chemical Additives

Without food science and the shortcuts taken by Big Food and Big Pharma corporations, we could not sustain our present standard of living, nor feed ourselves- our masses as we do. Not too long ago, almost all edible foods came from farms. Today’s food however is largely produced in factories. This processed factory food is chock full of questionable chemicals and additives. Be assured that most of these additives are safe from a chemist’s perspective. Intermittently however, new research uncovers dangers and unintended consequences associated with ingestion of these ‘safe’ food additives.

Sodium phosphate commonly encountered as approved STP (Sodium Tripolyphosphate) allows meat to hold more water. This is good for the seller who pumps this stuff into meat and bad for the buyer who must purchase meat by weight. To be fair, phosphates do help extend the shelf life of meat and dairy products like cheese by restricting the development of rancidity. Phosphates are under suspicion however of increasing the risk of kidney disease, high blood pressure and heart disease.

Sodium Lactate also increases meat shelf life and can be expected to benefit color and taste.

Sodium Erythorbate, Erythorbic Acid and Sodium Isoascorbate are added to meat to preserve its color. Keeping meat pink is a big thing; carbon monoxide gas is also used for this purpose as were sodium or potassium nitrites before the 1970’s.

Monosodium Glutamate (MSG) is an amino acid that makes meat and other food taste better. It allows companies to perhaps put less real meat into packaged food. Irregardless to brain damage caused to mice, baby- food makers of the 1960s put MSG into those little jars to influence the taste buds of parents.

Potassium Sorbate and Sorbic Acid inhibit mold growth on jerky, sausages, cheese, syrup & jelly.

Sodium Citrate which is a crystalline salt derived from citric acid fermentation or by the neutralization of citric acid with sodium hydroxide. It’s been recently approved for use in meat products as a preservative where it slows spoilage from microorganisms. Salty and tart in taste – it maybe used to flavor soft drinks and juices or be employed as an emulsifier.

Hydrolyzed vegetable proteins are used as Meat Flavor Intensifiers (MFI) and boost or increase the meaty flavor of meat items, gravies, and sauces.

Ractopamine hydrochlorid is not a chemical added to meat. Rather it is a growth enhancer, fed to livestock, which increases profits by requiring less feed. Quickly grown cattle fed this growth enhancer develop lean meat. Chickens and turkeys fed stuff like this often develop over-sized hearts, kidneys and livers, and grow so fast and get so heavy that they become immobile and cannot carry their own weight. Cattle and pigs fed a diet of ractopamine have developed abnormal lameness, bloat, breathing disorders and hoof disorders. Approved in countries like the U.S., Canada, Mexico, Japan and S. Korea – ractopamine hydrochlorid enhanced meats are outlawed in the EU, China and Russia.

Transglutaminase (TG or TGase) is an enzyme that bonds protein molecules together. First identified in 1959, it took another 30 years to find an economical source and exploit this ‘meat glue’. “With meat glue you can glue any protein to any protein”. “Gluing chicken skin to salmon works quite well….. and will actually protect the outside of the salmon from overcooking”. <Frankensteined meat>

Saltpeter can refer to several separate substances, most of which were strategic materials for making propellants and explosives in the 18th & 19th centuries. Sodium nitrate (NaNO3) is the compound most usually identified as a meat preservative, but also potassium nitrate and magnesium nitrate to lesser degrees. While regular table salt (NaCl) kills many bacteria like salmonella below 3% solution, much higher concentrations might be needed needed to kill other types of bacteria. A concentration of about 20% salt soaked into meat would be required to make meat safe from most every type of microbe. Meat that salty is not palatable. Somewhere back in time before the Romans, people noted that salt from certain mines preserved meat better, retained its color and made it taste better. Eventually traces of nitrate (saltpeter) were identified within that or those popular mined salt(s). The nefarious Clostridium botulinum bacterium was identified in 1895. Thereabouts it was determined that nitrate salts kill or inhibit the botulism causing bacteria. Since saltpeter also benefits color retention and imparts a desirable flavor we have been using nitrate meat preservatives every since; up until the 1999 that is.

The U.S. FDA has determined that nitrates are no longer allowed in commercially packed meats, while nitrites are to a limited small degree (for dry cured uncooked products like jerky). Nitrates and nitrites differ by one oxygen atom. Ammonia is released into the soil by the decomposition of organic matter, and it oxidizes to form a nitrate or nitrite. Nitrates themselves are relatively inert and enzymes in the human body convert them into nitrites anyway. Some vegetables we eat daily are loaded with nitrates, containing far more nitrates that might be encountered in cured meats. Some athletes might drink nitrate rich beet juice to enhance physical performance. Nitrites can turn into useful nitrous oxide by losing an oxygen atom or into dangerous nitrosamines, which can be created by high heat cooking. In the 1970s several studies showed correlations between nitrosamines and cancer in rats. Since that time, nitrates in curing salts have been studied to an exhaustive degree. The verdict is that nitrates and nitrites are not carcinogenic. Apparently nitrosamine formation can be inhibited by ascorbic acid. Since refrigeration is fairly ever-present today, there no sense in risking the possibility of someone creating nitrosamines by overcooking -uncooked nitrate cured meat. Individuals wishing to hard cure meat by traditional means can still buy premixed ‘salt cures’ containing either nitrites or nitrates or both. “Prague powder” is one such cure that is still sold after being invented 80 years ago.

USDA Ham and Food Saftey information.

Smoke

There are two widely separated forms of meat smoking. The old way of smoking for long term preservation – is now referred to as “cold smoking”. The new and widely spreading fad or form of meat smoking encountered these days is called “hot smoking”.

Hot smoking implies drenching meat in humid, flavorful smoke while simultaneously cooking the meat. Temperatures between 130 and 210 deg F are required for hot smoking. Since the cheaper and relatively tough cuts of meat are used in this process, the cooking is done slowly; taking a long time under moist heat to breakdown and soften the cartilage or gristle (collagen). Done correctly those tough cuts become very tender to chew. Hardwoods like oak, hickory, apple and cherry produce the most flavorful smoke. Depending upon the fuel used to create cooking heat (wood fire, propane, gas, electric) the smoke might be generated by pellets or moistened wood chips. Hot smoking is purely concerned with the art and science of cooking delicious, flavorful meat. It does not impart a preservative effect upon the meat.

Cold smoking has been going on for thousands of years, and for more practical reasons too when considering the historical lack of refrigeration. Wood smoke imparts preservative creosote to the meat that discourages insects and microorganisms alike. Wood smoke flavor in an aged hard cured ham or bacon might be intense, but still of a secondary nature when compared to the typical saltiness of that same dehydrated meat. “Virginia hams” were and still are famous for their flavor but these are often so salty that they need to be soaked and rinsed for 3 days to get the salt out.

Speaking of Virginia hams, Martha Washington (wife of the first American president) was famous for hers. The plantation at Mount Vernon was typical for plantations of the period. In addition to a large number of working residents to feed daily, guest and foreign dignitaries were always dropping in for visits. Martha reportedly set a good table. She also took pride in her hams, oversaw their curing process and shipped many away as gifts, some across the ocean. Two hundred years ago working plantations like this had crews to maintain large continually smoking smokehouses, which were packed with beef, pork, mutton, ducks, geese, fish and anything else they could find.

Famous uncooked, hard cured, smoked Virginia hams are available for purchase. These and some others like them are intended to be cooked, however some even more prominent European hard cured hams are usually eaten raw and are still allowed to be imported to the U.S. (Ardennes Ham from Belgium, Jamon Iberico & Jamon Serrano from Spain, Prosciutto from Italy, Westphalian Ham from Germany and sometimes York Ham from England – for example).

I am neither a chemist, physician nor an authority on the safety of consuming uncooked meats. All I can do is observe and realize that decisions made while preserving meat in traditional ways, do carry some risk and should not be made lightly.

Somehow this particular post took a detour and became somewhat longish. The title will be truncated from “Curing meats & Tanning hides” to what you see now. The last image from the post preceding this one featured a tiny homemade cold smoking apparatus featuring a venturi. The background of that fabricated image features a (lost) drawing of an industrial smokehouse, the type of which might have been found in any city of size, before artificial refrigeration was realized. Wood smoke was also used to preserve leather, a trick American ‘Indians’ were fond of. Rawhide and leather though, are fodder for a future post.

* (Update Oct 2019) – some highlighted or colored text was changed to make it more readable – for smartphones and the like, which insist upon changing the intended background color from charcoal, to white instead.

thanks to the author for taking his clock time on this one.

Good post. I study something more difficult on totally different blogs everyday. It can all the time be stimulating to read content material from different writers and apply a bit one thing from their store. I’d want to make use of some with the content material on my weblog whether or not you don’t mind. Natually I’ll offer you a link in your web blog. Thanks for sharing.